Written by Omanisa Ross (Peter’s great niece)

A few weeks before my great uncle Peter died, my mother interviewed him about his childhood and recorded the conversation. Last night we listened to the recording, eyes blurry with tears that came from laughter as much as grief. Even at the age of three he was independent adventurer who stubbornly defied authority and did exactly what he wanted to do: There’s space between where the two trams come, so I can ride my bike up there… I still laugh when I imagine the astonished look on the tram drivers’ faces at the sight of this tiny three-year old with bright red hair, merrily peddling his tricycle over the tram tracks.

34 years later, in 1967, Peter’s sense of adventure drew him to a teaching job in one of the most remote schools in Australia. His passion for the outback has lasted a lifetime, but the teaching job at Alice Springs Highschool only lasted six months. Having originally graduated with a double degree in maths and music in the mid 1950’s, Peter decided it was time to reinvent himself. Before going back to NSW University to study science, he climbed the Rock and fell in love: he’d found his spiritual home and knew he wanted to come back. Not far into his degree he discovered botany and fell in love a second time. “I didn’t find my calling until I was 40 years old” he often told me. “It’s never too late.”

Born in Tasmania in 1930, Peter grew up in Melbourne and moved to NSW to finish his schooling at the age of 19. Peter’s parents met at university while studying metallurgy, and they cultivated a deep love of learning and social service in their 6 children. When Peter finished his science degree in 1972, he’d been hoping to get work as a botanist at the Rock, but all that was available was a job teaching science to children at Papunya. It wasn’t what he had in mind, but it was an exciting time in Peter’s life, nonetheless. He shared a house with art teacher Geoff Bardon who was instrumental in getting the Papunya Tula art movement going, quickly becoming enthused with Geoff’s work.

When Geoff’s health broke down and he was admitted to hospital a few months later, Peter began working with the painters voluntarily, outside of school hours. It soon became clear that Geoff wasn’t returning, and Peter was appointed manager of the newly established painter’s company, Papunya Tula Artists Pty Ltd. “I didn’t have qualifications in art, but I was very articulate and the movement needed someone like that to speak for it. There followed the most hectic years of my life.”

As anthropologist Dick Kimber explains in his book Genesis and Genius, Peter purchased paintings to maintain the artists’ enthusiasm, “spent his own savings on vehicle maintenance and emergency support of the artists and their families; and drove himself almost literally into the ground to make things work… In the end, the pressures became intolerable, and Peter – this very fine person who had done so much at a crucial time- left in mid 1975.”

After Peter recovered his health, he found work as a labourer and field assistant at the Rock, for the NT Reserves Board and the Territory Parks and Wildlife Commission. He was over-qualified, and much to his employer’s exasperation, stubbornly insisted on creating Uluru-Kata Tjuta’s first herbarium, whether they liked it or not. In 1978 he began conducting his famous botanical ‘plant walks’ for tourists visiting The Rock, and by 1983 he had collected over 700 plant specimens for the informal herbarium.

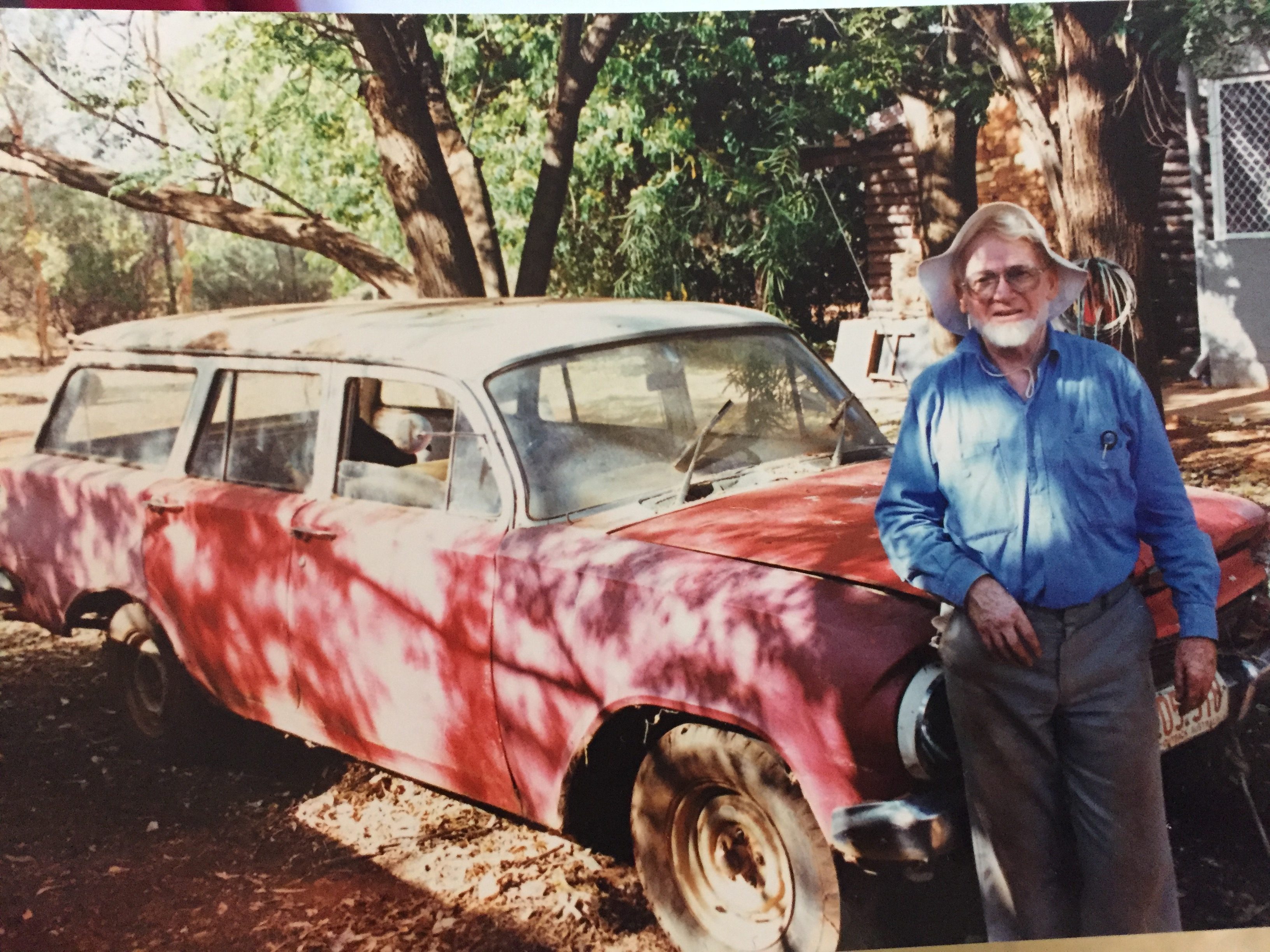

During most of his time at the Rock, Peter lived at the Aboriginal community of Mutitjulu, affectionately known by the locals as “Tjilpi Fannin” (‘respected elder man’ in Pitjantjatjara). When my brother and I came to stay during school holidays, Peter told us dreamtime stories, taught us about bush tucker and showed us how to find planets and constellations in the sky. There was always a tube of araldite in his top pocket, (because araldite can fix anything), and next to the araldite was a tin whistle he would whip out on a whim to play for us. We adored Flap, his yellow ultralight glider and Flowerpower, his maroon EJ Holden.

When Peter’s caravan fell apart he lived for many years in a tent, finally upgrading to a demountable in 1991. Even after selling his million-dollar collection of Papunya art to the Australian National Gallery in 1998, Peter stayed in his humble abode. He caused quite a stir when he returned much of the money he received back to the original artists and established a trust fund from which artists’ families received royalties. Peter had worked hard over many years to find the right home for the painting. He wanted to make sure the collection stayed together, to “brighten up the lives of all people and to point out the respect due to Aboriginal culture”.

In 2006, Peter was named as a national finalist for Australian of the Year, with the National Australia Day Council describing Peter as a “botanist, conservationist, astronomer, art lover, teacher and, most of all, a contributor to the community… instrumental in encouraging Indigenous Australians to express their culture through painting, leading to the world renowned, watershed Papunya art movement.” In 2011, Peter was included in the “Who’s Who in Australia” and finally, in 2013, he was acknowledged by park management, after 37 long years, for his “huge and continuing contribution.”

In 2015 Peter had to leave his beloved Rock and move to Old Timers in Alice for health reasons. We were devastated for him, but so pleased we had a chance to spend more time with him and return some of the love and support he had given to us over the years. “I’ve decided to leave my money to Papunya Tula Artists when I die,” Peter told me one day. In the meantime, he got busy with generous donations, including a thank you gift to Royal Flying Doctors, $100,000 for the creation an Indigenous Apprenticeship fund at Olive Pink Botanical Gardens to help them get on top of the buffel grass problem, and $100,000 to help Incite Arts establish an Indigenous Music Program at Yuendumu. And in amongst it all, he was endlessly generous with us, his family members, coming to our rescue in times of need, and fostering our studies, our careers and our dreams.

What I’m going to miss the most about my great uncle Peter are the conversations we used to have. With his passing, I have lost a mentor and one of my best friends. I loved the way his amazing brain could see connections between things that others could not, and the endless compassion of his beautiful heart.